Daft Punk

| Daft Punk | |

|---|---|

Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo in 2013 | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | France |

| Genres | |

| Discography | |

| Years active | 1993–2021 |

| Labels |

|

| Spinoff of | Darlin' |

| Past members | |

| Website | daftpunk |

Daft Punk were a French electronic music duo formed in 1993 in Paris by Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo. They achieved early popularity in the late 1990s as part of the French house movement, combining elements of house music with funk, disco, techno, rock and synth-pop.[1] They are regarded as one of the most influential acts in dance music.[2]

Daft Punk formed after Bangalter and de Homem-Christo's indie rock band, Darlin', disbanded. Their debut album, Homework, was released by Virgin Records in 1997 to positive reviews, backed by the singles "Around the World" and "Da Funk". From 1999, Daft Punk assumed robot personas for public appearances, with helmets, outfits and gloves to disguise their identities. They made few media appearances. They were managed from 1996 to 2008 by Pedro Winter, the head of Ed Banger Records.

Daft Punk's second album, Discovery (2001), earned acclaim and further success, with the hit singles "One More Time", "Digital Love" and "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger". It became the basis for an animated film, Interstella 5555, supervised by the Japanese artist Leiji Matsumoto. Daft Punk's third album, Human After All (2005), received mixed reviews, though the singles "Robot Rock" and "Technologic" were successful in the UK. Daft Punk directed an avant-garde science-fiction film, Electroma, released in 2006. They toured throughout 2006 and 2007 and released the live album Alive 2007, which won a Grammy Award for Best Electronic/Dance Album; the tour is credited for broadening the appeal of dance music in North America. Daft Punk composed the score for the 2010 film Tron: Legacy.

In 2013, Daft Punk left Virgin for Columbia Records and released their fourth and final album, Random Access Memories, to acclaim. The lead single, "Get Lucky", reached the top 10 in the charts of 27 countries. Random Access Memories won five Grammy Awards in 2014, including Album of the Year and Record of the Year for "Get Lucky". In 2016, Daft Punk gained their only number one on the Billboard Hot 100 with "Starboy", a collaboration with The Weeknd. Rolling Stone ranked them the 12th-greatest musical duo of all time in 2015, and included Discovery and Random Access Memories on their list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. Daft Punk announced their split in 2021.

History

[edit]1987–1992: Early career and Darlin'

[edit]

Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo and Thomas Bangalter met in 1987 while attending the Lycée Carnot secondary school in Paris.[3][4] The two became friends and recorded demos with others from the school.[5][6] In 1992, they formed a band, Darlin', with Bangalter on bass, Homem-Christo on guitar,[5][6] and Laurent Brancowitz on guitar and drums.[7] The trio named themselves after the Beach Boys song "Darlin'", which they covered along with an original composition.[7] Both tracks were released on a multi-artist EP under Duophonic Records, a label owned by the London-based band Stereolab, who invited Darlin' to open for shows in the United Kingdom.[7]

Darlin' disbanded after around six months, having played two gigs and produced four songs. Bangalter described the project as "pretty average".[8] Brancowitz formed another band, Phoenix.[8] Bangalter and Homem-Christo formed Daft Punk and experimented with drum machines and synthesizers.[citation needed] The name was taken from a negative review of Darlin' in Melody Maker by Dave Jennings,[9] who dubbed their music "a daft punky thrash".[10] The band found the review amusing.[4] Homem-Christo said, "We struggled so long to find [the name] Darlin', and [this name] happened so quickly."[11]

1993–1996: First performances and singles

[edit]

In September 1993, Daft Punk attended a rave at EuroDisney organised by the DJ Nicky Holloway, where they met Stuart Macmillan of Slam, the co-founder of the Scottish label Soma Quality Recordings.[4][12] They gave him a demo tape, which formed the basis for Daft Punk's debut single, "The New Wave", a limited release in 1994.[8] The single also contained the final mix of "The New Wave" called "Alive", which appeared on Daft Punk's first album.[13]

Daft Punk returned to the studio in May 1995 to record "Da Funk". After it became their first commercially successful single, they hired a manager, Pedro Winter, who regularly promoted them and other artists at his Hype nightclubs.[6] They signed with Virgin Records in September 1996 and made a deal to license tracks through their production company, Daft Trax.[3][6] Bangalter said that while they received numerous offers from record labels, they wanted to wait and ensure that they did not lose creative control. He considered the deal with Virgin more akin to a partnership.[14]

In the mid-to-late nineties, Daft Punk performed live at various events, without the costumes they later became known for. In 1996, they made their first performance in the United States, at an Even Furthur event in Wisconsin.[15] In addition to live original performances, they performed in clubs using vinyl records from their collection. They were known for incorporating numerous styles of music into their DJ sets.[16]

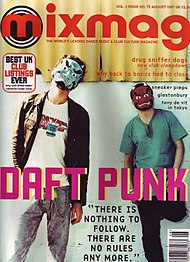

1997–1999: Homework

[edit]Daft Punk released their debut album, Homework, in 1997.[12] That February, the UK dance magazine Muzik published a Daft Punk cover feature and described Homework as "one of the most hyped debut albums in a long long time".[17] According to The Village Voice, the album revived house music and departed from the Eurodance formula.[18] The critic Alex Rayner wrote that it combined established club styles and the "burgeoning eclecticism" of big beat.[19] In 1997, Daft Punk embarked on an international concert tour, Daftendirektour, using their home equipment for the live stage.[8] On 25 May, they headlined the Tribal Gathering festival at Luton Hoo, England, with Orbital and Kraftwerk.[20]

The most successful single from Homework was "Around the World". "Da Funk" was also included on The Saint film soundtrack. Daft Punk produced a series of music videos for Homework directed by Spike Jonze, Michel Gondry, Roman Coppola and Seb Janiak. The videos were collected in 1999 as D.A.F.T.: A Story About Dogs, Androids, Firemen and Tomatoes.

Bangalter and Homem-Christo created their own record labels, Roulé and Crydamoure, after the release of Homework, and released solo projects by themselves and their friends. Homem-Christo released music as a member of Le Knight Club with Eric Chedeville, and Bangalter released music as a member of Together with DJ Falcon and founded the group Stardust with Alan Braxe and Benjamin Diamond. In 1998, Stardust released their only song, the chart hit "Music Sounds Better With You".[21]

1999–2003: Discovery

[edit]Daft Punk's second album, Discovery, was released in 2001. They said it was an attempt to reconnect with the playful, open-minded attitude associated with the discovery phase of childhood.[7] The album reached No. 2 in the UK, and its lead single, "One More Time", was a hit. The song is heavily autotuned and compressed.[7] The singles "Digital Love" and "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger" were also successful in the UK and on the US Dance Chart, and "Face to Face" hit number one on the US club play charts.

Discovery created a new generation of Daft Punk fans. It also saw Daft Punk debut their distinctive robot costumes; they had previously worn Halloween masks or bags for promotional appearances.[22] Discovery was later named one of the best albums of the decade by publications including Pitchfork[23] and Resident Advisor.[24] In 2020, Rolling Stone included it at number 236 in its list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time".[25] In 2021, Pitchfork cited Discovery as the centrepiece of Daft Punk's career, "an album that transcended the robots' club roots and rippled through the decades that followed".[26]

Daft Punk partnered with the Japanese manga artist Leiji Matsumoto to create Interstella 5555, a feature-length animation set to Discovery. The first four episodes were shown on Toonami in 2001, and the finished film was released on DVD in 2003.[27] That December, Daft Punk released Daft Club, a compilation of Discovery remixes.[28] In 2001, Daft Punk released a 45-minute excerpt from a Daftendirektour performance as Alive 1997.[29]

2004–2007: Human After All and Alive 2007

[edit]

In March 2005, Daft Punk released their third album, Human After All, the result of six weeks of writing and recording.[30] Reviews were mixed, with criticism for its repetitiveness and darker mood.[31] "Robot Rock", "Technologic", "Human After All" and "The Prime Time of Your Life" were released as singles. A Daft Punk anthology CD/DVD, Musique Vol. 1 1993–2005, was released on 4 April 2006. Daft Punk also released a remix album, Human After All: Remixes.[32]

On 21 May 2006, Daft Punk premiered a film, Daft Punk's Electroma, at the Cannes Film Festival sidebar Director's Fortnight.[33] The film does not include Daft Punk's music. Midnight screenings were held in Paris theaters from March 2007.[34]

For 48 dates across 2006 and 2007, Daft Punk performed the Alive 2006/2007 world tour, performing a "megamix" of their music from a large LED-fronted pyramid. The tour was acclaimed[35] and is credited for bringing dance music to a wider audience, especially in North America.[36][37] The Guardian journalist Gabriel Szatan likened it to how the Beatles' 1964 performance on The Ed Sullivan Show had brought British rock and roll to the American mainstream.[36]

Daft Punk's performance in Paris was released as their second live album, Alive 2007, on 19 November 2007.[38] The live version of "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger" was released as a single,[39] with a video by Olivier Gondry comprising audience footage of their performance in Brooklyn.[40] In 2009, Daft Punk won Grammy Awards for Alive 2007 and its single "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger".[41]

2008–2011: Tron: Legacy

[edit]

In 2007, Kanye West sampled "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger" in his single "Stronger". Daft Punk made a surprise appearance at the 50th Grammy Awards on 10 February 2008, and performed a reworked version of "Stronger" with West at the Staples Center in Los Angeles.[42] It was the first televised Daft Punk live performance.[42]

In 2008, Daft Punk returned to Paris to work on new material. Winter also stepped down as their manager to focus attention on his Ed Banger Records label and his work as Busy P.[43] He said later that Daft Punk were working with an unspecified management company in Los Angeles. Daft Punk held their Daft Arts production office at the Jim Henson Studios complex in Hollywood.[44] Daft Punk provided new mixes for the 2009 video game DJ Hero, and appeared as playable characters.[45]

At the 2009 San Diego Comic-Con, it was announced that Daft Punk had composed 24 tracks for the film Tron: Legacy.[46] Daft Punk's score was arranged and orchestrated by Joseph Trapanese.[47] The band collaborated with him for two years on the score, from pre-production to completion. The score features an 85-piece orchestra, recorded at AIR Lyndhurst Studios in London.[48] Joseph Kosinski, director of the film, referred to the score as a mixture of orchestral and electronic elements.[49] Daft Punk also make a cameo as disc jockey programs wearing their trademark robot helmets within the film's virtual world.[50] The soundtrack album was released on 6 December 2010.[51] A music video for "Derezzed" premiered on the MTV Networks on the same day the album was released.[52] The video, which features Olivia Wilde as the character Quorra in specially shot footage, along with images of Daft Punk in Flynn's Arcade, was later made available for purchase from the iTunes Store and included in the DVD and Blu-ray releases of the film. Walt Disney Records released a remix album, Tron: Legacy Reconfigured, on 5 April 2011.[53]

In 2010, Daft Punk were admitted into the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, an order of merit of France. Bangalter and Homem-Christo were individually awarded the rank of Chevalier (knight).[54] On October of that year, Daft Punk made a surprise guest appearance during the encore of Phoenix's show at Madison Square Garden in New York City. They played a medley of "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger" and "Around the World" before the song segued into Phoenix's song "1901". They also included elements of their tracks "Rock'n Roll", "Human After All", and "Together", one of Bangalter's releases as a member of Together.[55] They produced N.E.R.D.'s 2010 song "Hypnotize U".[56]

2011–2015: Random Access Memories

[edit]

In 2011, Soma Records released a previously unpublished Daft Punk track, "Drive", recorded while they were signed to Soma in the 1990s. It was included in a 20th-anniversary compilation of the Soma label.[57] In October 2012, Daft Punk provided a 15-minute mix of songs by blues musician Junior Kimbrough for Hedi Slimane's Yves Saint Laurent fashion show.[58] Daft Punk recorded their fourth studio album, Random Access Memories, with musicians including Julian Casablancas, Todd Edwards, DJ Falcon, Panda Bear, Chilly Gonzales, Paul Williams, Pharrell Williams, Chic frontman Nile Rodgers and Giorgio Moroder.[59][60][61][62][63][64] Daft Punk left Virgin for Sony Music Entertainment through the Columbia Records label.[65]

Random Access Memories was released on 17 May 2013.[66] The lead single, "Get Lucky", became Daft Punk's first UK number-one single[67] and the most-streamed new song in the history of Spotify.[68] At the 2013 MTV Video Music Awards, Daft Punk debuted a trailer for their single "Lose Yourself to Dance" and presented the award for "Best Female Video" alongside Rodgers and Pharrell.[69] In December, they revealed a music video for the song "Instant Crush", directed by Warren Fu and featuring Casablancas.[70]

At the 56th Annual Grammy Awards, Random Access Memories won the Grammy for Best Dance/Electronica Album, Album of the Year and Best Engineered Album, Non-Classical, while "Get Lucky" received the Grammy for Best Pop Duo/Group Performance and Record of the Year. Daft Punk performed at the ceremony with Stevie Wonder, Rodgers, Pharrell, and the Random Access Memories rhythm players Nathan East, Omar Hakim, Paul Jackson, Jr. and Chris Caswell.[71] That night, Daft Punk hosted a large Grammys afterparty at the Park Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles, with many celebrities and no photography allowed.[72][73]

Daft Punk co-produced Kanye West's sixth studio album, Yeezus (2013),[74] creating the tracks "On Sight", "Black Skinhead", "I Am a God" and "Send It Up" with West.[75] They provided additional vocals for Pharrell's 2014 single "Gust of Wind".[76] On 10 March 2014, an unreleased Daft Punk song, "Computerized", leaked online. It features Jay-Z and contains "The Son of Flynn" from the Tron: Legacy soundtrack;[77] it was once intended to be a single promoting Tron: Legacy.[78] In April 2015, Daft Punk appeared in a short tribute to Rodgers as part of a documentary on his life, Nile Rodgers: From Disco to Daft Punk.[79] In June, a documentary, Daft Punk Unchained, was released.[80]

2016–2020: Final projects and appearances

[edit]

Daft Punk appeared on the 2016 singles "Starboy" and "I Feel It Coming" by Canadian R&B singer the Weeknd;[81][82] "Starboy" topped the Billboard Hot 100, becoming Daft Punk's only US number-one song, and "I Feel It Coming" reached number four.[83][84] In 2017, Soma Records released a remix of "Drive" by Slam as part of a compilation featuring various artists.[85] In February 2017, Daft Punk launched a pop-up shop in Hollywood, California, featuring memorabilia, artwork, and a display of their costumes.[86] They also performed with the Weeknd at the 59th Annual Grammy Awards on 12 February 2017.[87]

In the years following the Starboy collaborations, Bangalter and Homem-Christo worked solo as producers appearing on several projects.[88][89][90][91] On 21 June 2017, the Australian band Parcels released the song "Overnight", produced and co-written by Daft Punk.[92] It was written after Daft Punk saw Parcels perform and invited the members to their studio. This became Daft Punk's final production together.[93]

Between 9 April and 11 August 2019, an electronic exhibition based on Daft Punk's song "Technologic" was displayed at the Philharmonie de Paris, featuring costumes, guitars and other elements.[94] In early 2024, W. F. Quinn Smith, who played percussion on Random Access Memories, said he had participated in experimental recording sessions for a new Daft Punk album in early 2018, but that the project was in limbo.[95]

2021–present: Disbandment and aftermath

[edit]On 22 February 2021, Daft Punk released a video on their YouTube channel titled "Epilogue".[96] The video features a scene from their 2006 film Electroma, in which one robot explodes and the other walks away into the sunset; a title card created with Warren Fu reads "1993–2021" while an excerpt of Daft Punk's song "Touch" plays.[96][1] Later that day, Daft Punk's longtime publicist, Kathryn Frazier, confirmed that they had split, but did not give a reason.[1] The news led to a surge in Daft Punk sales, with digital album purchases rising by 2,650%.[97] Their friend and collaborator Todd Edwards confirmed that Bangalter and Homem-Christo remained active separately.[98] He later said they were "going in different directions", and that Homem-Christo was more drawn to hip-hop and Bangalter was interested in film.[99] As of 2023, Bangalter and Homem-Christo still shared a studio and equipment.[100]

On 22 February 2022, one year after their disbandment, Daft Punk announced a 25th-anniversary edition of Homework. It included a remix album, Homework (Remixes), which was also released separately. Daft Punk also broadcast a Twitch stream of their performance at the Mayan Theater in Los Angeles from their 1997 Daftendirektour. The video featured previously unreleased footage of the duo without costumes. Daft Punk released behind-the-scenes "archives" from the D.A.F.T. DVD and album reissues throughout 2022.[101]

On 12 May 2023, Daft Punk released a 10th-anniversary edition of Random Access Memories, with 35 minutes of previously unreleased outtakes and demos. "Infinity Repeating (2013 Demo)", featuring Casablancas and the Voidz, was released as a single.[102][103] It was released alongside a music video and was called Daft Punk's "last song ever" in press releases.[104] On 17 November, Daft Punk released a version of Random Access Memories with no drums or percussion.[105]

In April 2023, Bangalter released a solo work, the orchestral ballet score Mythologies. He gave interviews about the project and allowed himself to be photographed without a mask. He cited concerns about the progress of artificial intelligence and other technology as to why Daft Punk split, saying: "As much as I love this character, the last thing I would want to be, in the world we live in, in 2023, is a robot." Bangalter said Daft Punk had wanted to not "spoil the narrative" while they were active, but now felt more comfortable revealing parts of their creative process.[106][100] Reflecting on the split, Bangalter said he was "relieved and happy to look back and say: 'Okay, we didn't mess it up too much.'"[107]

On 22 February 2024, the third anniversary of their split, Daft Punk announced a Twitch broadcast of Interstella 5555: The 5tory of the 5ecret 5tar 5ystem.[108] A vinyl repress of the Discovery single "Something About Us" was released on Record Store Day in April 2024.[109] A 4K remaster of Interstella 5555 premiered in June at Tribeca Festival.[110] The remaster was shown in global theaters for one weekend only in December.[9]

Artistry

[edit]Musical style

[edit]Daft Punk's musical style has been described as house,[111][112] French house,[112] electronic,[22] dance,[112][113] and disco.[112][22] Sean Cooper of AllMusic described it as a blend of acid house, techno, pop, indie rock, hip hop, progressive house, funk, and electro.[112]

The Guardian critic Alexis Petridis described their approach as magpie-like, with extensive sampling.[36] Homem-Christo described it as bricolage, the art of using found sounds to create new work.[114] Bangalter said in 2008: "I think that sampling is always something that we've completely legitimately done. It's not something we've hidden, it's almost a partisan or ideological way of making music, sampling things and being sampled ... It's always been a way to reinterpret things—sometimes it's using [an] element from the past, or sometimes recreating them and fooling the eyes or the ears, which is just a fun thing to do."[115]

According to Pitchfork, some fans were disappointed to discover that Daft Punk used samples.[116] In 2007, Rapster released Discovered: A Collection of Daft Funk Samples, a compilation of tracks sampled by Daft Punk.[116] Pitchfork wrote: "If [the compilation] proves anything, it isn't that Daft Punk are surreptitious thieves — it's that they're transformative reinterpreters, and in more than a few cases, flat-out miracle workers."[116] Daft Punk also used vintage equipment to recreate sounds by older artists, such as the use of a Wurlitzer piano to evoke Supertramp on "Digital Love".[117] They saw their style as retrofuturist, incorporating genres from earlier decades into what the New York Times described as "an increasingly grand vision of joyful populism".[100]

In the early 1990s, Daft Punk drew inspiration from rock and acid house in the UK. Homem-Christo referred to Screamadelica by Primal Scream as the record that "put everything together" in terms of genre.[118] In 2009, Bangalter named Andy Warhol as one of Daft Punk's early influences.[119] On the Homework track "Teachers", Daft Punk list musicians who influenced them, including the funk musician George Clinton, the rapper and producer Dr Dre, and Chicago house and Detroit techno artists including Paul Johnson,[36] Romanthony and Todd Edwards.[7] Homem-Christo said: "Their music had a big effect on us. The sound of their productions—the compression, the sound of the kick drum and Romanthony's voice, the emotion and soul—is part of how we sound today."[7]

Discovery integrates influences from 70s disco and 80s crooners, and featured collaborations with Romanthony and Edwards. A major inspiration was the 1999 Aphex Twin single "Windowlicker", which Bangalter said was "neither a purely club track nor a very chilled-out, down-tempo relaxation track".[120] For the Tron: Legacy soundtrack, Daft Punk drew inspiration from Wendy Carlos, the composer of the original Tron film, as well as Max Steiner, Bernard Herrmann, John Carpenter, Vangelis, Philip Glass and Maurice Jarre.[121][122] For Random Access Memories, Daft Punk sought a "west coast vibe", referencing acts such as Fleetwood Mac, the Doobie Brothers and the Eagles,[123] and the French electronic musician Jean Michel Jarre.[124][7]

Many Daft Punk songs feature vocals processed with effects and vocoders including Auto-Tune, a Roland SVC-350 and the Digitech Vocalist.[7] Bangalter said: "A lot of people complain about musicians using Auto-Tune. It reminds me of the late '70s when musicians in France tried to ban the synthesiser. They said it was taking jobs away from musicians. What they didn't see was that you could use those tools in a new way instead of just for replacing the instruments that came before. People are often afraid of things that sound new."[7]

Image

[edit]For most public and media appearances, Daft Punk wore costumes that concealed their faces.[125] Bangalter said they wanted the focus to be on their music,[126] and that masks allowed them to control their image while retaining their anonymity and protecting their personal lives.[8] He said that the 1974 film Phantom of the Paradise, in which the main character prominently wears a mask, was "the foundation for a lot of what we're about artistically".[127][128] Daft Punk were also fans of the 1970s band Space, who wore space suits with helmets that hid their appearance.[129] The mystery of Daft Punk's identity and their elaborate disguises added to their popularity.[118]

Daft Punk wore masks during promotional appearances in the 1990s.[22] Although they allowed a camera crew to film them for a French arts program at the time, Daft Punk did not speak on screen.[130] According to Orla Lee-Fisher, the head of marketing at Virgin Records UK, in their early career Daft Punk would only consent to photographs without masks while they were DJing.[131] In 1997, Bangalter said they had a rule to not appear in videos.[126]

In 2001, Daft Punk began wearing robot costumes for promotional appearances and performances for Discovery, debuted in a special presentation during Cartoon Network's Toonami block.[132] The helmets were produced by Paul Hahn of Daft Arts and the French directors Alex and Martin,[133] with engineering by Tony Gardner and Alterian, Inc. They were capable of various LED effects.[134] Wigs were originally attached to both helmets, but Daft Punk removed them moments before unveiling them.[22] Bangalter said the helmets were hot but that he became used to this.[135] Later helmets were fitted with ventilators to prevent overheating.[136] The costumes were compared to the makeup of Kiss and the leather jacket worn by Iggy Pop.[135]

With the release of Human After All, Daft Punk wore simplified helmets and black leather jackets and trousers designed by Hedi Slimane.[118] Bangalter said Daft Punk did not want to repeat themselves and were interested in "developing a persona that merges fiction and reality".[7] On the set of Electroma, Daft Punk were interviewed with their backs turned, and in 2006 they wore cloth bags over their heads during a televised interview.[137] They said the use of cloth bags had been a spontaneous decision, reflecting their willingness to experiment with their image.[138] Daft Punk wore their robot costumes in their performances at the 2008, 2014, and 2017 Grammy Awards. During the 2014 ceremony, they accepted their awards on stage in the outfits, with Pharrell and Paul Williams speaking on their behalf.[139][87]

Daft Punk used the robot outfits to merge the characteristics of humans and machines.[140] Bangalter said that the personas were initially the result of shyness, but that they became exciting for the audience, "the idea of being an average guy with some kind of superpower".[118] He described it as an advanced version of glam, "where it's definitely not you".[118] After Daft Punk's split, Bangalter likened the robot personas to a "like a Marina Abramović performance art installation that lasted for 20 years".[106] He denied that the robots represented "an unquestioning embrace of digital culture", and said: "We tried to use these machines to express something extremely moving that a machine cannot feel, but a human can. We were always on the side of humanity and not on the side of technology."[106]

Media appearances

[edit]

Daft Punk's popularity has been partially attributed to their appearances in mainstream media.[118] They appeared with Juliette Lewis in an advertisement for Gap, featuring the single "Digital Love", and were contractually obliged to appear only in Gap clothing. In 2001, Daft Punk appeared in an advertisement on Cartoon Network's Toonami timeslot, promoting the official Toonami website and the animated music videos for their album Discovery.[132] The music videos later appeared as scenes in the feature-length film Interstella 5555: The 5tory of the 5ecret 5tar 5ystem, in which Daft Punk make a cameo appearance as their robot alter-egos. They appeared in a television advertisement wearing their Discovery-era headgear to promote Sony Ericsson's Premini mobile phone. In 2010, Daft Punk appeared in Adidas advertisements promoting a Star Wars clothing line.[141] Daft Punk made a cameo in Tron: Legacy as nightclub DJs.[50]

In 2011, Coca-Cola distributed limited edition bottles designed by Daft Punk.[142] Daft Punk and Courtney Love were photographed for the "Music Project" of the fashion house Yves Saint Laurent. They appeared in their new sequined suits custom-made by Hedi Slimane, holding and playing instruments with bodies made of lucite.[143][better source needed] In 2013, Bandai released Daft Punk action figures coinciding with the release of Random Access Memories in Japan.[144] Daft Punk made a rare public appearance at the 2013 Monaco Grand Prix in May on behalf of the Lotus F1 Team, who raced in cars emblazoned with the Daft Punk logo.[145][146]

Footage of Daft Punk's 2006 performance at the Coachella Festival was featured in the documentary film Coachella: 20 Years in the Desert, released on YouTube in April 2020.[147] Daft Punk were scheduled to appear on 6 August 2013 episode of The Colbert Report to promote Random Access Memories, but this was canceled because of contractual obligations regarding their appearance at the 2013 MTV Video Music Awards. According to Stephen Colbert, Daft Punk were unaware of the agreement and were halted by MTV executives the morning prior to the taping.[148] In 2015, Daft Punk appeared alongside several other musicians to announce their co-ownership of the music service Tidal at its relaunch.[149]

Eden, a 2014 French drama film, has as its protagonist a techno fan-turned-DJ-turned recovering addict. It features Daft Punk (portrayed by actors) during different stages of their careers.[150] Daft Punk also appear in Pharrell Williams's 2024 biographical film Piece by Piece.[151]

Legacy

[edit]Daft Punk are regarded as one of the most influential dance acts.[152][153][2] The chief Guardian music critic Alexis Petridis named them the most influential pop artists of the 21st century.[2] Their collaborator Pharrell Williams said they were responsible for the rise of contemporary EDM, though Bangalter was noncommittal about this, saying only that other acts were using "gimmicks that at the time [Daft Punk used them] were not really gimmicks".[2] The New York Times credited Daft Punk with helping make dance music mainstream.[100] In 2015, Rolling Stone ranked Daft Punk the 12th-greatest musical duo.[154] In 2008, Daft Punk were voted the 38th-greatest DJs in a worldwide poll by DJ Mag.[155]

In "Losing My Edge", the first single by LCD Soundsystem, the singer James Murphy jokingly bragged about being the first to "play Daft Punk to the rock kids".[156] LCD Soundsystem also recorded the song "Daft Punk Is Playing at My House", which reached No. 29 in the UK and was nominated for Best Dance Recording at the 2006 Grammy Awards.[157]

Daft Punk tracks have been sampled or covered by other artists. "Technologic" was sampled by Swizz Beatz for the Busta Rhymes song "Touch It". In a later remix of "Touch It" the line "touch it, bring it, pay it, watch it, turn it, leave it, start, format it" from "Technologic" was sung by the rapper Missy Elliott. Kanye West's 2007 song "Stronger" from the album Graduation borrows the melody and features a vocal sample of Daft Punk's "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger". Daft Punk's robotic costumes appeared in the music video for "Stronger".[39] The track "Daftendirekt" from Daft Punk's album Homework was sampled for the Janet Jackson song "So Much Betta" from her 2008 album Discipline.[158]

The track "Aerodynamic" was sampled for Wiley's 2008 single "Summertime".[159] "Veridis Quo" from Discovery was sampled for the Jazmine Sullivan song "Dream Big" from her 2008 album Fearless.[160] Daft Punk's "Around the World" was sampled for JoJo's 2009 song "You Take Me (Around the World)". The song "Cowboy George" by the Fall contains a clip of "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger".[161] The a cappella group Pentatonix performed a medley of Daft Punk songs.[162] As of November 2021, the video had been viewed over 355 million times. The medley won for Best Arrangement, Instrumental or a Cappella of the 57th Grammy Awards.[163]

A Daft Punk medley was played at the 2017 Bastille Day parade by a French military band, in front of French President Emmanuel Macron and his many guests, which included United States President Donald Trump.[164][165] Baicalellia daftpunka, a species of flatworm, was named after Daft Punk in 2018 because part of the organism resembles a helmet.[166] In February 2024, Madame Tussauds New York unveiled their wax figures of Daft Punk.[167][168]

Discography

[edit]- Studio albums

- Homework (1997)

- Discovery (2001)

- Human After All (2005)

- Random Access Memories (2013)

Concert tours

[edit]- Daftendirektour (1997)

- Alive 2007 (2006–07)

Awards and nominations

[edit]In October 2011, Daft Punk placed 28th in a "top-100 DJs of 2011" list by DJ Magazine after placing in the 44th position the year before.[169][170] On 19 January 2012, Daft Punk ranked No. 2 on Mixmag's Greatest Dance Acts of All Time, with The Prodigy at No. 1 by just a few points.[171]

Bibliography

[edit]- Tony Gaenic, Daft Punk de A à Z, l'Étudiant, les guides MusicBook, 2002, p. 115, ISBN 978-2-84343-088-6

- Violaine Schütz, Daft Punk, l'histoire d'un succès planétaire, Scali, 2008, ISBN 978-2-35012-236-6

- Stéphane Jourdain, French Touch, le Castor Astral, Castormusic, 2005, p. 189, ISBN 2-85920-609-4

- Philippe Poirrier, Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco. Revival culturel à l'heure du numérique, French Cultural Studies, 2015, p. 381

- Peter Shapiro, Modulations, une histoire de la musique électronique, éditions Allia, 2004, p. 340, ISBN 978-2-84485-147-5

- Pauline Guéna, Anne-Sophie Jahn, DAFT, Éditions Grasset, 2022, p. 216, ISBN 9782246820390

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Coscarelli, Joe (22 February 2021). "Daft Punk Announces Breakup After 28 Years". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d Petridis, Alexis (23 February 2021). "Daft Punk were the most influential pop musicians of the 21st century". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 May 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Daft Punk Musique Vol. 1 Official Website". Archived from the original on 10 April 2006.

- ^ a b c "Daft Punk" (in French). RFI Musique. 3 December 2007. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Daft Punk : De l'école des "raves" à Homework". metamusique.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d James, Martin (2003). French Connections: From Discotheque to Discovery. London: Sanctuary Publishing. pp. 265, 267, 268. ISBN 1-86074-449-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Chris Gill, "Robopop" Archived 3 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine (May 2001) Remix Magazine Online. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Collin, Matthew (August 1997). "Do You Think You Can Hide From Stardom?". Mixmag. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- ^ a b Raggett, Ned (14 May 2013). "Blog post by Ned Raggett". Ned Raggett's Blog. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ "Review of Shimmies in Super 8". Melody Maker. April–May 1993.

- ^ Di Perna, Alan (April 2001). "We Are The Robots". Pulse!. pp. 65–69.

- ^ a b Daft Punk in Glasgow: Slam on 'the two quiet wee guys' who used to crash on their sofa Archived 27 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Jules Boyle, Glasgow Live, 24 February 2021

- ^ "The New Wave" (12" vinyl liner notes). Daft Punk. UK: Soma Quality Recordings. 1994. SOMA 14.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "Yahoo! Music Interviews". Yahoo! Music. 30 December 2010. Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Daft Punk, live at Even Furthur 1996 Archived 22 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine driftglass.org. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^ Lisa Verrico, "Masked Groove-Riders", Blah Blah Blah (February 1997).

- ^ Bush, C. (1997), Frog Rock, Muzik, IPC Magazines Ltd, London, Issue No.21 February 1997.

- ^ Woods, Scott (5 October 1999). "Underground Disco?" Archived 9 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. The Village Voice. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Rayner, Alex (2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. p. 812. New York, NY: Universe Publishing. 2006. ISBN 0-7893-1371-5. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ 2 Cents: Kraftwerk, Tribal Gathering Archived 8 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine (25 May 1997). Retrieved 7 February 2007.

- ^ "Stardust's 'Music Sounds Better With You': Remastering & Revisiting Classic Single 20 Years Later". Billboard. 13 June 2018. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Weiner, Jonah (21 May 2013). "Daft Punk: All Hail Our Robot Overlords". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ "The Top 200 Albums of the 2000s: 20-1". Pitchfork. 2 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ "Top 100 albums of the '00s". Resident Advisor. 25 January 2010. Archived from the original on 14 August 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ "Pitchfork Reviews: Rescored". Pitchfork. 5 October 2021. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ "Daft Punk's Anime Masterpiece, Interstella 5555, Is Here to Stay". CBR. 25 February 2021. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "CD: Daft Punk, Daft Club". the Guardian. 28 November 2003. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Alive 1997 (liner notes). Daft Punk. Virgin Records, a division of Universal Music Group. 2001.

- ^ Human After All liner notes (2005). Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ^ "Human After All – How Daft Punk's most maligned album warned of the perils of progress". The Independent. 14 March 2020. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Daft Punk - Human After All ~原点回帰 -Remixes-, 17 June 2014, archived from the original on 3 June 2023, retrieved 3 June 2023

- ^ Daft Punk's Electroma review Archived 12 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Variety. Retrieved 26 February 2007.

- ^ Daft Punk's Electroma Screenings Info Archived 9 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine (in French) allocine.fr. Retrieved 11 April 2007.

- ^ Jenkins, Craig (24 February 2021). "Daft Punk Gave Us More Than Enough Time". Vulture. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d Szatan, Gabriel (26 February 2021). ""They left an indelible mark on my psyche": how Daft Punk pushed pop forward". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Nabil. "Cover Story: Daft Punk". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Exclusive: Daft Punk Unveil Live Album Details; Midlake to Release EP Archived 25 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine Spin. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- ^ a b Live Album To Chronicle Daft Punk Tour Billboard. Retrieved 17 August 2007. Archived 21 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Daft Punk Announce Live Album Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine side-line.com. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ "51st Annual GRAMMY Awards (2008)". Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Daft Punk Make Surprise Grammy Appearance with Kanye West Archived 2 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine NME. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- ^ Daft Punk Are Back in the Studio Archived 13 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine inthemix.com. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- ^ Tron: Legacy's' orchestral score reveals a new side of Daft Punk Archived 26 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (22 February 2021). "DJ Hero was the closest thing we got to a Daft Punk game". Polygon. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "SDCC: Comic-Con: Disney 3D Hits Hall H!". 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ "Daft Punk's Classical Meets Cyberpunk Approach to "Tron: Legacy". culturemob.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ "Disney Awards 2010: Tron Legacy". The Walt Disney Company. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ "'Tron Legacy' Panel Report, Fresh From San Diego Comic-Con". MTV. 23 July 2009. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Details of Daft Punk's Tron: Legacy Cameo". Pitchfork. 6 October 2010. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Official website of Tron Legacy's soundtrack Archived 25 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ "Review of Daft Punk's 'Derezzed' Music Video". MTV. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ "Disney TRON: LEGACY Hits The Grid – Tuesday, April 5th" (Press release). Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ "Daft Punk chevaliers des Arts et des Lettres !" Archived 11 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine by Laure Narlian, France 2 (24 August 2010). Retrieved 7 November 2010. (French)

- ^ "Daft Punk played w/ Phoenix @ Madison Square Garden (pics)". Brooklynvegan.com. 20 October 2010. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ "Daft Punk Produce New N.E.R.D. Track". Pitchfork. 9 September 2010. Archived from the original on 3 October 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ Breihan, Tom (3 August 2011). "Lost Daft Punk Track Unearthed". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ "Daft Punk unveil new blues mix listen". NME. 11 October 2012. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Listen: Lost Daft Punk Track "Drive"". Pitchfork. 16 September 2011. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Paul Williams on Hit Records Nightlife Video hosted by Eddie Muentes. 14 July 2010. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Sandler, Eric. "Disco legend Nile Rodgers talks about cancer, Broadway & his Daft P... – CultureMap Houston". CultureMap Houston. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ sarahanne (3 March 2012). "Chic on". Fasterlouder.com.au. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ "BREAKING :: Giorgio Moroder Recorded With Daft Punk". URB. 25 May 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Field Day Radio | Field Day Festival". Fielddayfestivals.com. 2 June 2012. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Daft Punk arrive chez Sony Archived 11 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine zik-zag.blog.leparisien.fr. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ Daft Life Limited (2013). "Random Access Memories Daft Punk View More By This Artist". iTunes Preview. Apple Inc. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ "Daft Punk score first UK number one single". BBC News. 28 April 2013. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Muston, Samuel (12 May 2013). "Disco 2.0: Following Daft Punk's 'Get Lucky', we've all caught Saturday Night Fever again". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ Ehrlich, Brenna (25 August 2013). "Video Music Awards – Daft Punk VMA Appearance: The Robots Finally Emerge". MTV. Archived from the original on 29 August 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ Danton, Eric R. (6 December 2013). "Daft Punk Melt Hearts in 'Instant Crush'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "Daft Punk and Stevie Wonder Lead Funky Disco Smash-Up at Grammys". Rolling Stone. 26 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Aswad, Jem (1 February 2024). "Ten Years Ago, Daft Punk Threw a Legendary, Star-Studded Grammy Party — and Hardly Anyone Recognized Them". Variety. Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Zemler, Emily (27 January 2014). "Grammys: Daft Punk Takes Off Helmets, Celebrates Big Wins With Star-Studded Dance Party". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Levine, Nick (6 June 2013). "Daft Punk confirmed as co-writers of new Kanye West track 'Black Skinhead'". NME. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "Kanye West's Yeezus features Daft Punk, TNGHT, Justin Vernon, and Chief Keef". Consequence of Sound. 11 June 2013. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ Pharrell Williams, G I R L liner notes (2014).

- ^ "Daft Punk – Computerized (Ft. Jay Z)". indieshuffle. Archived from the original on 5 April 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Disney, Oh My (9 September 2016). "Computerized: The Never-Before-Told Story of How Disney Got Daft Punk For TRON Legacy". Oh My Disney. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Camp, Zoe (27 April 2015). "Daft Punk Make Tribute Video for Nile Rodgers". Pitchfork. Pitchfork Media Inc. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "10 things we learned from Daft Punk Unchained". the Guardian. 29 June 2015. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Robinson, Will (21 September 2016). "The Weeknd, Daft Punk release Starboy single". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Iyengar, Rishi (21 September 2016). "Listen to the Weeknd's New Single 'Starboy' With Daft Punk". Time. Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "The Weeknd Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Archived from the original on 1 June 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Cook-Wilson, Winston (18 November 2016). "New Music: The Weeknd – "I Feel It Coming" ft. Daft Punk, "Party Monster" ft. Lana Del Rey". SPIN. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Bartleet, Larry (15 March 2017). "Slam: the Glasgow duo who signed Daft Punk talk 25 years of the Soma label and premiere their long-lost remix of Daft Punk's 'Drive'". NME. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Take a look inside Daft Punk's pop-up shop/retrospective Archived 2 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. 11 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ a b The Weeknd, Daft Punk Sing 'I Feel It Coming' at 2017 Grammys Archived 8 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Variety. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ "Daft Punk's Thomas Bangalter produced Arcade Fire's latest album". Mixmag. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ "Thomas Bangalter a co-produit un titre avec Matthieu Chedid". TSUGI (in French). 23 November 2018. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ "The Weeknd Releases New Album My Dear Melancholy,: Listen". Pitchfork. 29 March 2018. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ "Listen to Charlotte Gainsbourg's New Song "Rest", Made With Daft Punk's Guy-Manuel". Pitchfork. 7 September 2017. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ Parcels Team With Daft Punk on New Song "Overnight": Listen Archived 12 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ Kupfer, Rachel. ""Overnight" by Parcels Is Officially Daft Punk's Last-Ever Production: Listen". EDM.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Daft Punk, Kraftwerk & Electronic Icons Participate in Immersive Paris Exhibition". Hypebeast. 27 February 2019. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ Buckle, Becky (1 February 2024). "Daft Punk drummer says unreleased fifth album exists: 'They're working on it'". Mixmag. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ a b Daly, Rhian (22 February 2021). "Music world reacts to Daft Punk's split: "An inspiration to all"". NME. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Blake, Emily (24 February 2021). "Digital Love: Daft Punk Sales Soar 2,650% After Breakup". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "Interview: Todd Edwards on new single 'The Chant', what's next for Daft Punk, and the inspiration behind his productions". 909originals.com. 22 March 2021. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Duran, Anagricel (8 September 2023). "Daft Punk 'weren't on the same page anymore', says collaborator Todd Edwards". NME. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d Woolfe, Zachary (3 April 2023). "Daft Punk's Thomas Bangalter Reveals Himself: As a Composer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (22 February 2022). "Daft Punk to host one-time-only stream of 1997 helmetless show". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Daft Punk Announce New Random Access Memories Reissue With Unreleased Music". Pitchfork. 22 February 2023. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Daft Punk Share Previously Unreleased Julian Casablancas Collab "Infinity Repeating": Listen". Stereogum. 12 May 2023. Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ "Listen to the last Daft Punk song ever, "Infinity Repeating"". The FADER. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (28 September 2023). "Daft Punk continue accessing random memories with Drumless Edition LP". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Savage, Mark (3 April 2023). "Life after Daft Punk: Thomas Bangalter on ballet, AI and ditching the helmet". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 September 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Thomas Bangalter on ending Daft Punk: "I'm relieved to look back and say 'Ok, we didn't mess it up too much'"". Mixmag. Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ Bain, Katie (22 February 2024). "Daft Punk to Livestream Its 2003 Film 'Interstella 5555' in Honor of Daft Punk Day". Billboard. Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Pilley, Max (15 February 2024). "Record Store Day 2024: Check out the full list of releases". NME. Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Rettig, James (30 April 2024). "Tribeca Film Festival 2024 Adds Michael Stipe, Scorsese & De Niro In Conversation With Nas, Daft Punk's Interstella 5555, & More". Stereogum. Archived from the original on 7 May 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ Sayare, Scott (26 January 2012). "Electro Music Ambassador's French Touch". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Cooper, Sean. "Daft Punk AllMusic Bio". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Mason, Kerri (10 May 2013). "Daft Punk: How the Pioneering Dance Duo Conjured 'Random Access Memories'". Billboard. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Reesman, Bryan (1 October 2001). "Daft Punk". Mix. Archived from the original on 21 May 2006. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Nadeau, Cheyne; Nies, Jennifer (July–August 2013). "The Work of Art Is Controlling You". Anthem (29): 36–37. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Patrin, Nate (19 November 2007). "Various artists: Discovered: A Collection of Daft Funk Samples". Pitchfork. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ Bryan Reesman, Daft Punk interview Archived 10 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine Mix (magazine). Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Suzanne Ely, "Return of the Cybermen" Mixmag, July 2006, pp. 94–98.

- ^ Indrisek, Scott (Summer 2009). "Daft Punk: One half of Daft Punk, Thomas Bangalter, dishes on mixing high and low-brow culture with performance art". Whitewall Magazine (14): 91–99. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ "Daft Punk Embark On A Voyage of Discovery" MTVe.com. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ^ "Daft Punk's 'Legacy' act | Pop & Hiss". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "Daft Punk tell all about Tron: Legacy". FACT Magazine: Music News, New Music. 18 November 2010. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ TheCreatorsProject (8 April 2013). "The Collaborators: Todd Edwards" (Video upload). Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2013 – via YouTube.

- ^ Yenguin, Sam (18 June 2013). "Guest DJ: Daft Punk On The Music That Inspired 'Random Access Memories'". 89.9 WWNO. WWNO. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ Martin, Piers (4 December 2013). "Daft Punk: The Birth of The Robots". Vice. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ a b CANOE – JAM! Music – Artists – Daft Punk: Who are those masked men?[usurped] canoe.ca. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- ^ Daft Punk Gets Human With a New Album Archived 23 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ Jokinen, Tom (2 July 2013). "How Phantom of the Paradise is the Daft Punk Story". Hazlitt. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ The Moog Cookbook Were Daft Punk Before Daft Punk Archived 24 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. LA Weekly. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ 'Jockey Slut. Vol. 2, no. 1. April–May 1996. p. 55.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Cardew, Ben (2021). Daft Punk's Discovery: The Future Unfurled. London: Velocity Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-913231-11-8.

- ^ a b Toonami: Digital Arsenal Archived 14 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine toonamiarsenal.com. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ Diehl, Matt. Human After All, Indeed: The Best Daft Punk Interview You Never Read Archived 29 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. thedailyswarm.com. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ Liner notes of the Discovery album—"Bionics Engineering by Tony Gardner & Alterian"

- ^ a b Daft Punk and the Rise of the Parisian Nightlife Archived 27 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Paper Magazine. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ Les Inrockuptibles No. 910 (May 2013).

- ^ Daft Punk Talk Electroma. While Wearing Bags On Their Heads. Archived 8 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine twitchfilm.net. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- ^ Daft Punk Icelandic ELECTROMA Interview 2006 Archived 5 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine YouTube. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ Daft Punk wins big at Grammy Awards Archived 9 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. USA Today. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Daft Punk interview in Japan (1/2) Archived 28 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Daft Punk – Archives (26 November 2021). Daft Punk — Star Wars: Adidas Originals - Cantina (4K). Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Daft Punk to Team Up with Coca-Cola for, Um, Daft Coke". Exclaim!. 23 February 2011. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "Saint Laurent Music Project- Daft Punk". Archived from the original on 16 April 2013.

- ^ "魂ウェブ Daft Punk 魂ウェブ商店にて予約受注生産!!". Archived from the original on 30 August 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ Drewett, Meg (27 May 2013). "Daft Punk join up with Lotus F1 Team at Monaco Grand Prix". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

Lotus – who announced a partnership deal with Daft Punk's record label Columbia in March – raced in specially-branded cars emblazoned with the band's logo.

- ^ Daw, Robbie (28 May 2013). "Daft Punk Attend Grand Prix To Support The Lotus F1 Team, Who Do Not Get Lucky in the Race". Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

Daft Punk members Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo made a rare public appearance on Sunday (May 26) to support British Formula One team Lotus F1 at the Grand Prix in Monaco.

- ^ Juliano, Michael (31 March 2020). "The Coachella documentary is coming to fuel your personal Couchella party". TimeOut Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "Daft Punk Cancel 'Colbert Report' Appearance Due to Contractual Agreement With MTV VMAs". Pitchfork. 6 August 2013. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Tidal Owners Including Jay Z, Arcade Fire, Daft Punk, Kanye West, Jack White, & Madonna Share The Stage At Launch Event Archived 29 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Stereogum. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Kinos-Goodin, Jesse (11 September 2014). "TIFF 2014: Daft Punk's surprising role in French house music movie Eden". Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Jackson, Angelique (6 June 2024). "Pharrell Williams Debuts Trailer for His Lego Animated Biopic 'Piece by Piece' — and Teases Two New Tracks". Variety. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Daft Punk announce split after 28 years". BBC News. 22 February 2021. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ "Daft Punk's 10 best songs". NME | Music, Film, TV, Gaming & Pop Culture News. 22 February 2021. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ "20 Greatest Duos of All Time". Rolling Stone. 17 December 2015. Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ DJmag.com: Top 100 DJs – Results & History Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine djmag.com. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ "LCD Soundsystem - Losing My Edge Lyrics | Genius Lyrics". Genius. Archived from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "LCD Soundsystem". Grammy Awards. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ Janet Jackson Samples Daft Punk Archived 25 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine Stereogum. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- ^ Grime Music Cleans Up in the Charts Archived 2 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Independent. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- ^ Staff (7 November 2008). "Jazmine Sullivan – 'Dream Big'". Popjustice. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ "[Review/Listen] – The Fall – Your Future Our Clutter (2010)". ListenBeforeYouBuy. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Daft Punk – Pentatonix Archived 15 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. YouTube. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ 57th Annual GRAMMY Awards Nominees Archived 25 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ Reilly, Nick (14 July 2017). "Donald Trump forced to sit through Daft Punk medley during Bastille Day parade". NME. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ Video, Telegraph (14 July 2017). "French military band plays Daft Punk medley, leaving Donald Trump bemused". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Stephenson, India; Van Steenkiste, Niels W. L.; Leander, Brian S. (2018). "Molecular phylogeny of neodalyellid flatworms (Rhabdocoela), including three new species from British Columbia". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 57: 41–56. doi:10.1111/jzs.12243. ISSN 0947-5745. S2CID 91740559.

- ^ "Daft Punk: The Latest to 'Get Lucky' in New York - Madame Tussauds". 27 February 2024. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ "Daft Punk Wax Figures Unveiled at Madame Tussauds New York". Billboard. 27 February 2024. Archived from the original on 28 February 2024. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ DJ Mag Top 100 DJs of 2011 Archived 23 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine djmag.com. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ DJ Mag Top 100 DJs of 2012 Archived 19 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine djmag.com. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "Mixmag | Mixmag'S Greatest Dance Act of All Time Revealed". Archived from the original on 21 January 2012.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Daft Punk at IMDb

- Daft Punk discography at Discogs

- Daft Punk discography at MusicTea

- Daft Punk discography at MusicBrainz

- Daft Punk at AllMusic

- Daft Punk on Eurochannel

- Daft Punk

- 1993 establishments in France

- 2021 disestablishments in France

- Bands with fictional stage personas

- Brit Award winners

- French club DJs

- Columbia Records artists

- Electronica music groups

- Electronic music duos

- English-language musical groups from France

- French electronic music groups

- French house music groups

- French musical duos

- Grammy Award winners for dance and electronic music

- Lycée Carnot alumni

- Male musical duos

- Masked musicians

- Musical groups established in 1993

- Musical groups disestablished in 2021

- Musical groups from Paris

- Parlophone artists

- French remixers

- French dance music groups

- Virgin Records artists

- Walt Disney Records artists

- Warner Records artists